Author: Lucy McInally

Kicking off 2023, the London Coworking breakfast show last month involved a brilliant workshop on the topic of fundamental human needs in a working environment in exclusive spaces. Host Mark Catchlove separated us into groups with a task to define what matters most in the workplace. Our group all agreed that feeling a sense of belonging is truly important.

In a workspace, you either feel welcome or you don’t. You might be influenced by your coworkers, their personalities and interests that align with yours (or they don’t). Or maybe the lighting is (or isn’t) perfect, the amenities (are not) ideal, and the space (is not) accessible to you. Belongingness isn’t limited to working environments. Naturally, you want to feel comfortable in your own home. Public spaces should be inclusive too; when you’re walking down a street or hopping on a train, popping into a coffee shop or local supermarket. You don’t feel this way? These spaces haven’t been planned to meet your needs. Maybe they were designed a long time ago…

In the Medieval period, community life took place within the walls of the thriving city and in the public eye, where merchants sold their wares, and buskers sang and played instruments within the hustle and bustle of activity. This is where the CBD – central business district – originates from. A commercial town centre. The economic male activities of the city were separated from the domestic female interests of home life. Merchants, landowners and clergymen, largely male, had the say on how space was used and by whom. Beyond the city walls, land was either occupied by the Church or owned by the monarchy and used for hunting and recreation.

The 1604 Enclosure Act allowed greedy landowners to seize space on which they built impressive country dwellings which looked like Ancient Greek temples. The land surrounding it was cultivated to express the grand status of its occupants and marked by elaborate gates that controlled access.

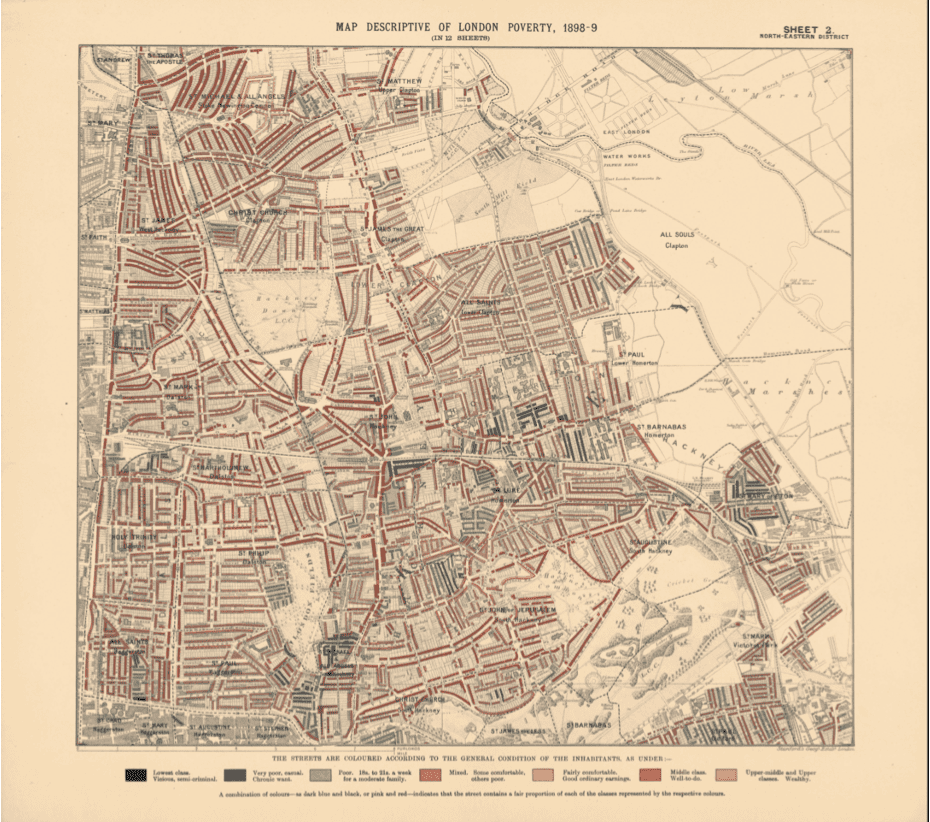

By the time of the Industrial Revolution, the British city became associated with technology and capitalism. Urbanisation took off big time; cities became dirty and overwhelmed, many workers lived in slum-like conditions of squalor. Poverty became associated with criminality. The creation of London poverty maps categorised low income families as “vicious”. The wealthy and emerging middle-classes labelled the poor “immoral”.

The Victorian city became so unhealthy that in the mid-1800s, a series of reforms were introduced to try and alleviate health and social conditions. Britain’s first council houses were built in 1869. The 1830 public parks movement led to the creation of open green sites that provided the lungs of the city. Parks were designed to control how people navigate space and interact with each other (ever wondered why pathways are so narrow?). Statues of glorified individuals popped up in public spaces to enlighten the “common people” to change their behaviours, status and thoughts.

A pledge of 500,000 “homes for heroes” was agreed to reward the working class who stepped up to defend their country after the first world war. More reforms were introduced to provide wider accessibility to healthcare, education and housing. The social housing schemes of the early to mid-twentieth century were designed to encourage human connection between neighbours. Flats often surrounded a central court and were linked together with external corridors known as “streets in the sky”. But this utopian version of community life was most likely the middle classes forcing their own expectations onto the working class.

The formation of eleven New Towns surrounding London in the 1940s encouraged Londoners to leave the overcrowded city, with promises of access to nature and village-like neighbourliness. It was an attempt to mix different social classes together. New Towns were originally planned around a village green – the centre of community life. Yet, budget constraints scrapped the green in favour of building more houses. Britain’s industry was in turmoil by the end of the 1970s. Factories shut down and the ports were left derelict. Thatcher deregulated the financial market, known as the Big Bang, and London became a global financial capital. Government and landowners sold space to private companies. Gated communities popped up in London’s financial districts, Docklands and the East End, to safely house its well paid workers.

In our contemporary world, private companies still hold a lot of power over space. For instance, Battersea Power Station, which stood empty since 1980, was bought by a group of Malaysian investment companies forty years later. Whilst the process of restoring the building to its former glory was considerate, the treatment of its people was not. The community has been priced out, replaced by individuals who bring more wealth to the area. A smattering of celebrities have snapped up the multi-million pound sky villas that top the power station. The revamped area includes a recently opened shopping mall, expensive restaurants and coffee shops, a pricey ice rink opens at Christmas and a costly fireworks show is held in November. The community is hailed “an inclusive neighbourhood”, but the people who once lived here have been displaced and can’t come back to the area they once called home. It’s too expensive. This space has not been developed for them. You might not feel it’s for you either.

So, no wonder you don’t feel comfortable when you walk across a square or through a park. Or you step into a store, or an office. This space hasn’t been designed for you, it was created for someone else. It might have been planned centuries ago. Or maybe it has been developed with you in mind, then perhaps you don’t feel excluded. Nonetheless, designers, developers and architects of current and future projects should do better. Users ought to challenge the way things are. If we all work together, listen to one another and understand each and every person’s needs, we could collaborate to build a better future that’s truly inclusive to all.

Sources and reading list

Most of the source content in this article comes from my Masters dissertation, and the books I used for research.

- Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar. The Park and the People: A History of Central Park. (1992, New York: Cornell University Press).

- Tom Williamson. Polite Landscapes: Gardens and Society in Eighteenth-Century England. (1995, Gloucester: Sutton Publishing).

- Tricia Kang. “160 Years of Central Park: A Brief History”.

- Suzie L. Steinbach. Understanding the Victorians: Politics, Culture and Society in Nineteenth-Century Britain (2012, London: Routledge).

- Maureen Flanaghan. Constructing the Patriarchal City: Gender and the Built Environments of London, Dublin, Toronto and Chicago. (2018, Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

- John Broughton. Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing. (2019, London: Verso).

- Anna Minton. Ground Control: Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First-Century City. (2012, London: Penguin Books).

- Lynsey Hanley. Estates: An Intimate History. (2012, London: Granta Books).